Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun | King Tut

Since his tomb was first discovered in 1922, the life of King Tut has continued to mystify and enthrall both historians and amateur sleuths alike. The young age of the ruler, his mysterious death and the curse that continues to be associated with ancient Egypt and King Tut have only increased the world's fascination with King Tut's life history. The mystery surrounding the young King Tut transformed him into the most famous of all Egyptian pharaohs. However, he was not considered a powerful or important leader during and after his reign. How did a young boy who was pharaoh for only nine years become the icon of Egyptian royalty? The Search for Tutankhamun

Archaeologists in the 20th century uncovered many tombs, coffins and funerary items in the Valley of the Kings at Thebes. The area was a popular research area for historians, scientists and wealthy investors. Historical texts left no records of the burial of King Tutankhamun. Archaeologists found several clues in the tombs of others that suggested that Tut was buried in the Valley. Between 1905 and 1908, Theodore Davis and Edward Aryton found three antiquities showing or referring to Tutankhamun's location in the Valley of the Kings. These few clues led Howard Carter on a search for the mysterious pharaoh. Ancient texts indicated that during his reign Tutankhamun had tried to return Egypt to a previous religious status. Carter saw this as an additional sign that Tut’s tomb would be found within the Valley of the Kings. The House of Howard Carter

The Discovery In November 1922, Howard Carter was facing his last chance for finding the tomb of King Tutankhamun. Four days into the final expedition, he positioned his workers at the base of the tomb of Ramesses VI. Workers exposed 16 steps leading to a resealed doorway. Carter had no doubt whose tomb he was entering. King Tut's name appeared everywhere.

© Tona & Yo - The Entrance to the Tomb of Tutankhamun The presence of a reseal meant that the tomb robbers had raided the tomb, but during ancient times. The interior revealed that the tomb had been entered and straightened, then resealed by Egyptian authorities. It appeared that the tomb had been untouched for thousands of years. After making their way through a never seen before amount of treasures, Carter and his team entered the antechamber. Two life-size wooden statues of King Tutankhamun stood guarding the burial chamber. Inside the chamber, they found the first intact royal burial to ever be uncovered by modern Egyptologists.

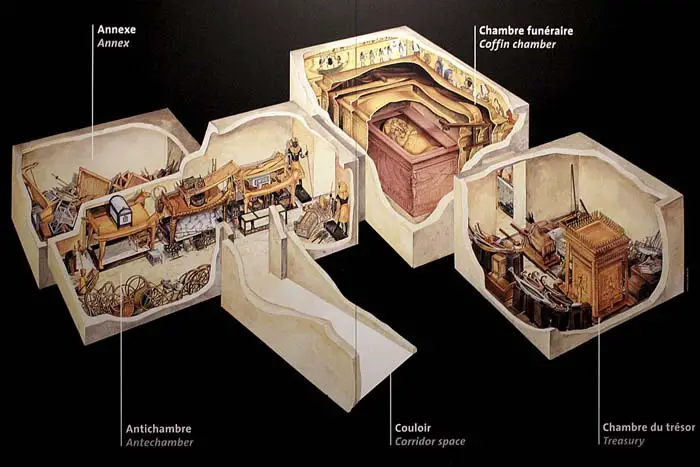

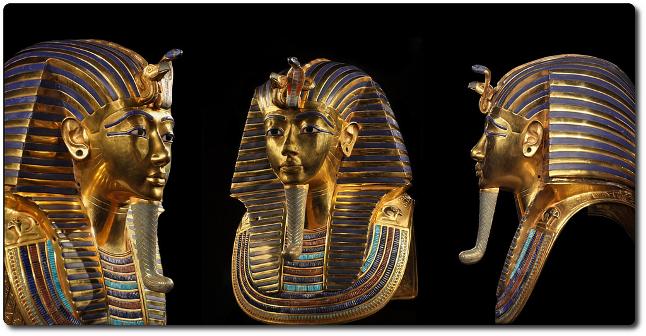

© Claude Valette - The Chambers of Tutankhamun's Tomb A Royal Mummy Like a nesting doll, the mummy of Nebkheperure Tutankhamun lay within four gilded funerary shrines. These shrines protected a stone sarcophagus. Inside the sarcophagus were three coffins. The two outside ones were gilded, while the inner one was made of gold. Inside these layers, Tut’s mummy lay covered with jewelry, amulets and a stunning death mask made of gold. Weighing a little over 10kg, the death mask portrays Tutankhamun as a god. He holds the crook and flail, symbols of the rule over Egypt, the nemes headdress, and the beard that associates the pharaoh with Osiris, thus highlighting the status of a deity.The mask is adorned with turquise and lapis lazuli, depictions of gods and goddesses, and a section from the Book of the Dead which the ancient Egyptian used as a map in their journey into the afterlife. Despite the huge impact the discovery would have in uncovering much about the life of royalty in ancient Egypt, King Tutankhamun’s tomb brought up many questions about his life, family tree and death. The answers to these questions remained hidden until many years after Carter’s death. King Tut's Death Mask Tutankhamun's so-called 'death mask' is the funerary mask he was buried with. It is a massive gold representation of King Tut, resembling other depictions of him archaeologists found in his tomb. The death mask is highly decorative, with inlays of colored glass, lapis lazuli and other gemstones, including quartz and obsidian for the eyes. The beard is a symbol of the pharaoh status - and a cause of recent trials, after a few museum workers damaged it. Luckily, a German-Egyptian team managed to restore it to its original aspect.

© Kačka a Ondra - Inner coffin of Tutankhamun Family Members Tutankhamun was born around 1343 BC. At this time, Egypt was already almost 2,000 years old. Egypt was in what historians call an “obscure” state. Researchers refer to this period at the end of the 18th dynasty as the post-Amarna period. Early in the research of Tut’s life, historians believed that he was of the Akhenaten family. A single reference at the great Aten temple at Tell el-Amarna told historians that Tutankhamun was most likely the son of Akhenaten and one of his many wives. Modern science has reportedly substantiated this claim. Scientists have tested the supposed body of the Pharaoh Akhenaten and compared it to Tutankhamun. DNA evidence supports Akhenaten is the father of Tutankhamun. In addition, the mummy of one of Akhenaten’s minor wives, Kiya, was linked through DNA as Tut’s mother. Further DNA testing reveals that Kiya, also known as the “Younger Lady,” was the daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye. This makes her a sister of Akhenaten. Inside of Tut’s tomb, scientists identified a lock of hair as belonging to his grandmother, Queen Tiye, the chief wife of Amenhotep III. Two mummified fetuses were also found within the tomb. DNA indicates that they were Tutankhamun’s children. Tutankhamun married his half-sister Ankhesenamun as a child. One of the earliest found antiquities pictures Tutankhamun giving his wife one of is enemies. Letters written by Ankhesenamun after Tut’s death say “I have no son,” indicating that Tut and his wife had no living children to carry on his legacy. Click here to discover more about King Tut's Family

© Asaf Braverman - Depiction of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun Reign of Tutankhamun Tutankhamun actually began his reign as Tutankhaten. He grew up in the royal harem, marrying his sister at an early age. At this point Ankhesenamun was known as Ankhesenpaaten. At the age of nine he was crowned pharaoh in Memphis. He would rule between 1332 and 1323 BC. The change in the names of the young pharaoh and his spouse are a result of the decision to return Egypt to an older religious practice which worship Amun instead of Aten. This reconciled the young couple with those who represented the former order of worship. In the second year of Tut’s rule, he moved the capital of Egypt from Akhenaten to Thebes and reduced the god Aten to a rarely mentioned god.

© Tjflex2 - Tutankhamun Statue at Thebes Tutankhamun died young, in only the ninth year of his rule. Estimates place him as 18 or 19 years old at the time of his death. Because Tut was just a child and ruled for such a short time, he left little impact on Egypt. He was under the protection of three men: the divine father Ay, the general Horemheb and the treasurer Maya. These men most likely made the majority of the decisions and influenced the pharaoh’s policies. The majority of the work completed on temples and shrines during the reign of Tutankhamun remained unfinished. Later pharaohs would complete work and replace Tut’s name with their own. For example, the Luxor temple at Thebes bears work accomplished during Tutankhamun’s rule. After Tut’s death, Horemheb’s name replaced Tut’s name on the temple, although the original version is still clear in some areas.

© Tjflex2 - Plaque at Thebes, depicting King Tut A Mysterious Death When King Tut’s mummy was first found, historians discovered trauma to the body. His mysterious death quickly led to many theories involving intrigue and murder among the Egyptian royals. How did he die? Was he murdered? Who murdered him?

© Nasser Nouri - The head of Tutankhamun's Mummy The first examinations by Howard Carter and a team led by Dr. Douglas Derry could not make a certain determination on the cause of death. The majority of Egyptologists believed that his death resulted from a fall from a chariot or other similar accident. Recently, an international research team under the leadership of Dr. Chris Naunton discovered injuries on one side of Tutankhamun's body, which led to the conclusion that King Tut was involved in a chariot crash, but further investigation concluded that this was highly unlikely. The search for a medical cause of death has revealed much about the life of Tutankhamun. He probably never enjoyed good health during his life. Scans reveal he suffered from a bone disorder combined with a club foot. Researchers believe Tut needed canes to walk. This explains the 139 ebony, ivory, silver and gold canes found within his tomb.

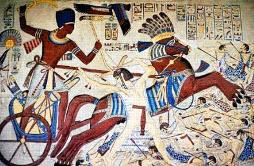

© Nasser Nouri - The Feet of Tutankhamun's Mummy Despite being a royal god-king of Egypt, he also suffered the same fate as many of his subjects: malaria. His body displays evidence of having endured several malarial infections during his short life. One of these infections, malaria tropica, is one of the most common forms of the disease. King Tut's Funeral The funeral of Tutankhamun, although similar to any funeral in ancient Egypt, involved much more lavish details due to his status as pharaoh of Egypt. Scholars estimate it to have taken place some time between February and April. The embalming process was the longest, believed to last several weeks. Embalmers removed the internal organs (buried in canopic jars along with the deceased), then dried the body with natron. They then applied a treatment of unguents, herbs and resin - a wider range of ointments than the lower classes would have been able to afford. The body of the young pharaoh was then covered in fine linen, not only to preserve his body, but also to shape it for the afterlife - the body that would live forever. Archaeologists found remains of the embalming process in the vicinity of Tutankhamun's tomb. This indicates that, perhaps, ancient Egyptians believed they kept a trace of the buried person. Vessels for water, although some small and frail, crafted with a symbolic purpose, are evidence for funeral rites of purification. The tomb also sheltered a variety of dishes, bowls and plates, that held food and drink offerings. These were buried with the pharaoh, so he would use them in the afterlife. King Tut's funeral included extravagant adornments of his tomb: mural paintings, chariots and everyday items for the afterlife, and gorgeous gold jewelry. There are also extremely well preserved remains of plants used for decorative purposes - olive branches, picris, rennet and blue cornflowers. Treasures of Ancient Egypt Howard Carter’s careful inventory of King’s Tut tomb combined with pictures taken by Harry Burton of New York’s Metropolitan Museum to reveal the amazing treasures buried with the young pharaoh. Ten years of work cataloging the massive number of items revealed that Tut's burial happened quickly in chambers smaller than usual for the size of his treasure.

© Photo Dean - Reproduction of Tutankhamun's Tomb Contents King Tutankhamun’s tomb was only 12.07 feet high, 25.78 feet wide and 101.01 feet long. Inside were over 3,000 separate items, most of pure gold. The antechamber was in complete disarray. Golden furniture and dismantled chariots lay piled into the area. The annex contained more furniture and jars of oil, ointments, food and wine. The burial chamber contained the golden layers of Tut’s coffin and the famous death mask. A treasury room, guarded by a statue of the god Anubis, contained jeweled chests, extravagant jewelry, model boats and a golden shrine containing the Canopic jars holding King Tut’s internal organs.

© Charlie Phillips - Canopic Jars of Tutankhamun Historians believe that Egyptian priests buried Tutankhamun within his tomb before the paint had time to dry on the walls. Microbial growth found on the walls of the tomb indicates to scientists that the paint was still wet when the tomb was sealed off from the world. Dark spots located on the tomb’s artwork are a result of the microbial growth and are now considered a unique feature. The small chambers, quick burial and ancient attempts at tomb robbing explain the chaotic conditions found within the tomb. It is most likely that Tut’s replacement, Ay, rushed his burial in order to smoothly take over the rule of Egypt. The Struggle for the Throne Despite the allure of a mysterious murder and the possible motives for such a powerful move, historians believe that those around Tutankhamun would not have wanted him to die early. He, along with his wife, were the last of the ruling dynasty. Coming from a family not known for health and longevity, Tut's advisors would have worried about his life. Only through the royal pair were they able to hold power. They most likely would have protected the couple, trying to keep them from harm. Tut's wife, Ankhesenamun, was in a precarious position after his death. She was the last living member of Akhenaten’s family and left alone as the ruler of Egypt. She was young and surrounded by very ambitious older men. Letters show that she tried to save her husband’s legacy and her place on the throne by contacting the King of the Hittites. She asked him to send her a husband as protection. Otherwise, she indicates she will be forced to marry a servant. The prince began his journey, but unknown assassins killed him before he arrived. Ankhesenamun would marry the divine father Ay. He would rule Egypt for four years, only to be succeeded by General Horemheb. The Curse of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb The idea of a young, handsome King of Egypt dying a tragic, untimely death at the hands of a murderous fiend combined with a series of events following the discovery of his tomb to create the popular legend of Tut’s cursed tomb. Although the curse has been debunked many times by historians, popular culture has maintained that those who come into contact with Tut’s tomb will die. The story of the curse began with the death of Howard Carter’s benefactor, Lord Carnarvon, five months after the discovery of the tomb. He died from an infection as a result of a mosquito bite. It is reported that at the exact moment of his death all of the lights in Cairo went out. Other stories say that Lord Carnarvon’s beloved hound dog in England howled and dropped dead at the same time as the Lord’s death. Historians believe that the source of the curse rumors was bored newsmen covering the excavation of Tut’s tomb in combination with comments by the archaeologist Arthur Weigall. Prior to the discovery of Tut’s tomb, mummies were not considered cursed, but magical and healing

Ramesses II

Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE, alternative spellings: Ramses, Rameses) was known to the Egyptians as Userma’atre’setepenre, which means 'Keeper of Harmony and Balance, Strong in Right, Elect of Ra’. He is also known also as Ozymandias and as Ramesses the Great. He was the third pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty (1292-1186 BCE) who claimed to have won a decisive victory over the Hittites at The Battle of Kadesh and used this event to enhance his reputation as a great warrior. In reality, the battle was more of a draw than a decisive victory for either side but resulted in the world's first known peace treaty in 1258 BCE. Although he is regularly associated with the pharaoh from the biblical Book of Exodus there is no historical or archaeological evidence for this whatsoever. Ramesses lived to be ninety-six years old, had over 200 wives and concubines, ninety-six sons and sixty daughters, most of whom he outlived. So long was his reign that all of his subjects, when he died, had been born knowing Ramesses as pharaoh and there was widespread panic that the world would end with the death of their king. He had his name and accomplishments inscribed from one end of Egypt to the other and there is virtually no ancient site in Egypt which does not make mention of Ramesses the Great.

EARLY LIFE AND CAMPAIGNS

Ramesses was the son of Seti I and Queen Tuya and accompanied his father on military campaigns in Libya and Palestine at the age of 14. By the age of 22 Ramesses was leading his own campaigns in Nubia with his own sons, Khaemweset and Amunhirwenemef, and was named co-ruler with Seti. With his father, Ramesses set about vast restoration projects and built a new palace at Avaris. The Egyptians had long had an uneasy relationship with the kingdom of the Hittites (in modern-day Asia Minor) who had grown in power to dominate the region. Under the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (1344-1322 BCE), Egypt had lost many important trading centers in Syria and Canaan. Seti I recaptured the most coveted center, Kadesh in Syria, but it had been taken back by the Hittite king Muwatalli II (1295-1272 BCE). After the death of Seti I in 1290 BCE, Ramesses assumed the throne and at once began military campaigns to restore the borders of Egypt, ensure trade routes, and take back from the Hittites what he felt rightfully belonged to him. In the second year of his reign, Ramesses defeated the Sea Peoples off the coast of the NileDelta. According to his account, these were a people known as the Sherdan who were allies of the Hittites. Ramesses laid a trap for them by placing a small naval contingent at the mouth of the Nile to lure the Sherdan warships in. Once they had engaged the meager fleet, he launched his full attack from both sides, sinking their ships. Many of the Sherdan who survived the battle were then pressed into his army, some even serving as his elite bodyguard. The Sea Peoples' origin and ethnicity is unknown, although many theories have been suggested, but Ramesses describes them in his account as Hittite allies and this is important as it underscores the relationship between the Egyptians and Hittites at this time. At some point, prior to the year 1275 BCE, he began construction of his great city Per-Ramesses ("House of Ramesses") in the Eastern Delta region near to the older city of Avaris. Per-Ramesses would be his capital (and remain an important urban centre throughout the Ramesside Period), a pleasure palace, and a military compound from which he would launch campaigns into neighboring regions. It was not only an armory, military stable, and training ground but was so beautifully constructed that it rivalled the magnificence of the ancient city of Thebes. It is possible, as some scholars suggest, that Per-Ramesses was actually founded - and construction begun - by Seti I because it was already a functioning military centre by the time Ramesses II launched his campaigns in 1275 BCE. Ramesses marched his army into Canaan which had been a Hittite vassal state since the reign of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I. This campaign was successful and Ramesses returned home with plunder and Canaanite (and probably Hittite) royalty as prisoners. The historian Susan Wise Bauer comments on this: At twenty-five, the new pharaoh had already been living an adult life for at least ten years. He had married for the first time at fifteen or so, and had already fathered at least seven children. He had already fought in at least two of his father's campaigns up into the Western Semitic lands. He did not wait long before picking up the fight against the Hittite enemy. In 1275, only three years or so after taking the throne, he began to plan a campaign to get Kadesh back. The city had become more than a battle front; it was a symbolic foot-ball kicked back and forth between empires. Kadesh was too far north for easy control by the Egyptians, too far south for easy administration by the Hittites. Whichever empire claimed it could boast of superior strength (247). In late 1275 BCE, Ramesses prepared his army to march on Kadesh and waited only for the omens to be auspicious and word from his spies in Syria as to the enemy's strength and position. In 1274 BCE, when all seemed in his favor, he led some twenty thousand men out of Per-Ramesses into battle, the army divided into the four companies named after the gods: Amun, Ra, Ptah, and Set. Ramesses led the Amun division with the others following behind.

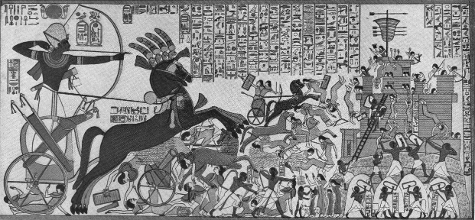

THE BATTLE OF KADESH

They marched for two months before reaching a place where he felt confident in arranging his army in battle formation for attack on the city and waited with his Amun division, along with his sons, for the others to catch up. At this time, two Hittite spies were captured who, under torture, gave up the location of the Hittite army which they said was nowhere near the city. Reassured, Ramesses abandoned his plans for an immediate strike and gave orders for his division to encamp and wait for the rest of the army to arrive. The Hittite army, however, was actually less than a mile away and the two spies had been purposefully sent. As Ramesses was pitching camp, the Hittites roared out from behind the walls of Kadesh and struck. The battle is described in Ramesses accounts, Poem of Pentaur and The Bulletin, in which he relates how the Amun division was completely overrun by the Hittites and the lines were broken. The Hittite cavalry was cutting down the Egyptian infantry and survivors were scrambling for the safety of their camp. Recognizing his situation, Ramesses called upon his protector god, Amun, and fought back. According to historian Margaret Bunson: Ramesses brought calm and purpose to his small units and began to slice his way through the enemy in order to reach his southern forces. With only his household troops, with a few officers and followers, and with the rabble of the defeated units standing by, he mounted his chariot and discovered the extent of the forces against him. He then charged the eastern wing of the assembled foe with such ferocity that they gave way, allowing the Egyptians to escape the net which Muwatalli had cast for them (131). Ramesses had only just turned the tide of battle when the Ptah division arrived and he quickly ordered them to follow him in the attack. He drove the Hittites toward the Orontes River killing many of them while others drowned trying to escape. He had not considered the position his hasty charge might place him in, however, and was now caught between the Hittites and the river. All Muwatalli II needed to do to win at this point was to send his reserve troops into battle and Ramesses and his army would have been destroyed; yet, for some reason, the Hittite king did not do this. Ramesses rallied his forces and drove the Hittites from the field. He then claimed a great victory for Egypt in that he had defeated his enemy in battle but the Battle of Kadesh nearly resulted in his defeat and death. According to his own reports, it was only owing to his own personal courage and calm in battle (and the goodwill of the gods) that he was able to turn the tide against the Hittites.

Ramesses II at The Battle of Kadesh

Ramesses II at The Battle of Kadesh

Rameses immortalized his feats at Kadesh in the Poem of Pentaur and The Bulletin in which he describes the battle as a dazzling victory for Egypt but Muwatalli II also claimed victory in that he had not lost the city to the Egyptians. The Battle of Kadesh led to the first peace treaty ever signed in the world between Ramesses II of Egypt and Muwatalli II's successor, Hattusili III (died 1237 BCE) of the Hittite Empire. After the Battle of Kadesh, Ramesses devoted himself to improving Egypt's infrastructure, strengthening its borders, and commissioning vast building projects commemorating his victory of 1274 and his other accomplishments.

QUEEN NEFERTARI & LATER LIFE

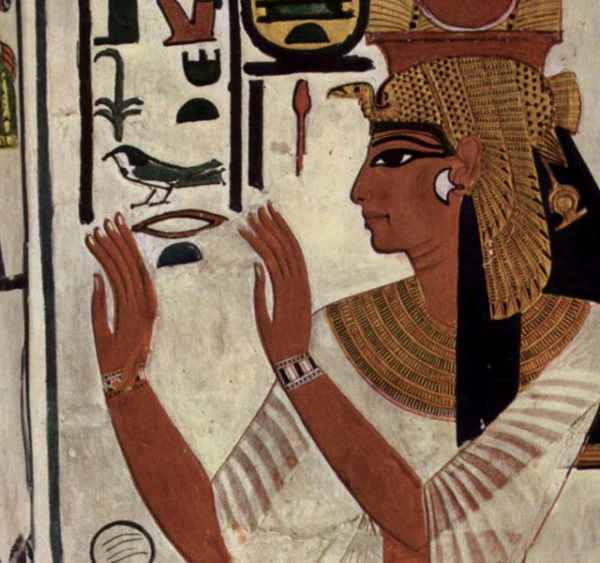

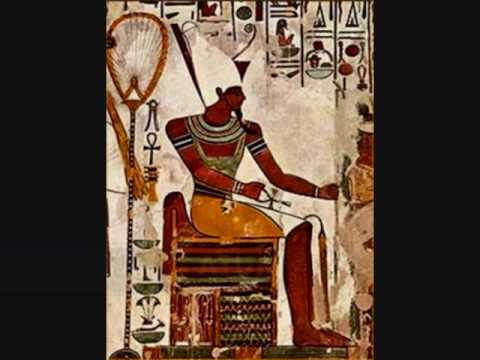

The vast tomb complex known as the Ramesseum at Thebes, the temples at Abu Simbel, the hall at Karnak, the complex at Abydos and literally hundreds of other buildings, monuments, temples were all constructed by Ramesses. Many historians consider his reign the pinnacle of Egyptian art and culture and the famous Tomb of Nefertari with its wallpaintings is cited as clear evidence of the truth of this claim. Nefertari was Ramesses' first wife and his favorite queen. Many depictions of Nefertari appear on temple walls and in statuary throughout his reign even though she seems to have died fairly early in their marriage (perhaps in child birth) and her tomb, even though discovered looted, was a work of art in construction and decoration.

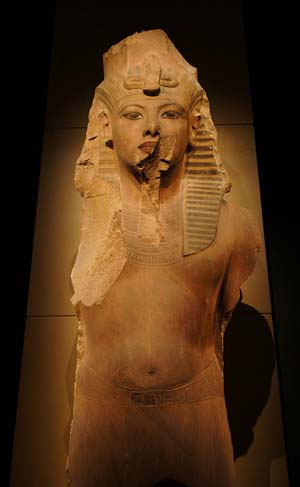

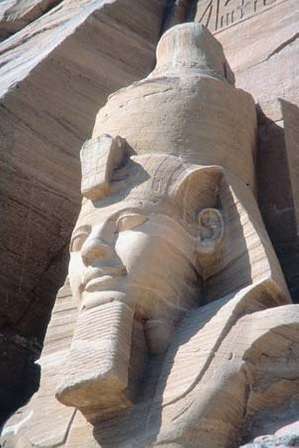

Ramesses II Statue

After Nefertari, Ramesses elevated his secondary wife Isetnefret to the position of queen and, after her death, his daughters became his consorts. Even so, the memory of Nefertari seems to have always been close in his mind in that Ramesses had her likeness engraved on walls and statuary long after he had taken other wives. He always treated the children of these wives with equal regard and respect. Nefertari was the mother of his sons Rameses and Amunhirwenemef and Isetnefret the mother of Khaemwaset and yet all three were treated the same.

RAMESSES AS PHARAOH OF EXODUS

Although Ramesses has been popularly associated with the pharaoh of the biblical Book of Exodus, there is absolutely no evidence to support this claim. The association of the name `Ramesses' with the unnamed pharaoh of Egypt in the Bible became quite common after the success of Cecil B. DeMille's film The Ten Commandments in 1956. Film versions of the biblical story since, including the popular animated film Prince of Egypt (1998) and the more recent Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) both followed the lead of DeMille's film but there is no historical support for this association. Exodus 1:11 and 12:37 as well as Numbers 33:3 and 33:5 all mention Per-Ramesses as one of the cities the Israelite slaves labored on and also the city they departed Egypt from. There is no evidence of a mass exodus from the city - nor from any other city in the history of Egypt - and none to support the claim that Per-Ramesses was built by slave labor. Extensive archaeological excavations at Giza and elsewhere throughout Egypt have unearthed ample evidence that the building projects completed under the reign of Ramesses II (and every other king of Egypt) used skilled and unskilled Egyptian laborers who were either paid for their time or who volunteered as part of their civic duty. The custom of Egyptian citizens volunteering their time to work on the king's building projects is well documented and it was even thought that, in the afterlife, souls would be called upon to work for Osiris, Lord of the Dead, on the building projects he would want. The practice of placing shabti dolls in the tombs and graves of the dead was precisely for this purpose: so the dolls would take the place of the deceased in work projects. Further, Ramesses was famous for recording histories of his accomplishments and for embellishing the facts when they did not quite fit history as he wished it preserved. It seems highly unlikely that such a king would neglect to record (with or without a favorable slant) the plagues which allegedly fell upon Egypt or the flight of the Hebrew slaves. One need not rely solely on the inscriptions Ramesses himself ordered, however; the Egyptians, from the time they mastered writing c. 3200 BCE, kept very extensive records and none of them even hint at a large population of Hebrew slaves in Egypt much less their mass exodus. Further, the literary works of the Egyptians from the Middle Kingdom through the Late Period provide numerous motifs, themes, and actual events which were made use of by the later scribes who wrote the biblical narratives. The association of Ramesses with the cruel, stubborn pharaoh of Exodus is unfortunate as it obscures the character of a man who was a great and noble ruler.

LEGACY

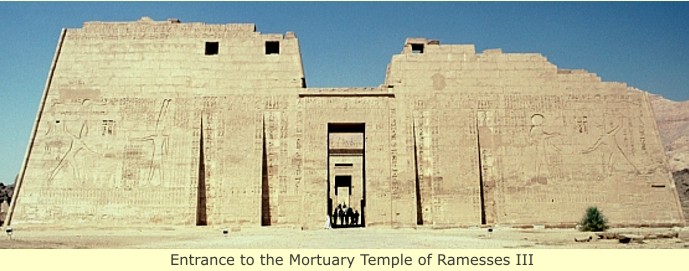

The reign of Ramesses II has become somewhat controversial over the last century with some scholars claiming he was more of a showman and a propagandist than and effective king and others arguing the opposite. The records of his reign, however - both the written and the physical evidence of the temples and monuments - argue for a very stable and prosperous reign. He was one of the few rulers to live and rule long enough to take part in two Heb Sed festivals which were held every thirty years to rejuvenate the pharaoh. He secured the country's borders, increased its wealth, and widened its scope of trade and, if he boasted of his accomplishments in his inscriptions and monuments, it is because he had good reason to be proud. Ramesses the Great’s mummy shows that he stood over six feet in height with a strong, jutting jaw, thin nose and thick lips. He suffered from dental problems, severe arthritis, and hardening of the arteries and, most likely, died from old age or heart failure. He was known to later Egyptians as the 'Great Ancestor’ and many pharaohs would do him the honor of taking his name as their own. Some of them, such as Ramessess III, are considered better rulers than he was; none of them, however, would surpass the grand achievements and glory of Ramesses the Great in the minds and hearts of the ancient Egyptians.

Ramses the Great: Black Man of the Nile and Pride of Africa

Although it was the African Sudan–the “Ethiopia” (Land of the Blacks) of ancient times–that gave birth to the oldest civilization, it is in Kmt (Ancient Egypt), a child of Ethiopia and greatest nation of antiquity, that the bulk of historical research has been done. For the moment, at least, Kmt continues to be the focal point of our African centered researches, and will probably be the object of much of our studies for some time to come. Not only were Ancient Egypt’s origins African, but through the entire Dynastic Age and during all the periods of real splendor from the initial unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in the fourth millennia B.C.E. men and women with black skin complexions and wooly hair reigned virtually supreme.

Although it was the African Sudan–the “Ethiopia” (Land of the Blacks) of ancient times–that gave birth to the oldest civilization, it is in Kmt (Ancient Egypt), a child of Ethiopia and greatest nation of antiquity, that the bulk of historical research has been done. For the moment, at least, Kmt continues to be the focal point of our African centered researches, and will probably be the object of much of our studies for some time to come. Not only were Ancient Egypt’s origins African, but through the entire Dynastic Age and during all the periods of real splendor from the initial unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in the fourth millennia B.C.E. men and women with black skin complexions and wooly hair reigned virtually supreme.

In the intense and unrelenting struggle to establish and prove scientifically the African foundations of ancient Egyptian civilization, the late Senegalese scholar Cheikh Anta Diop remains a most fierce and ardent champion. Diop, 1923-1986, was among the world’s leading Egyptologists, and held the position of Director of the Radiocarbon Laboratory of the Fundamental Institute of Black Africa in Dakar, Senegal. The range of methodologies employed by Dr. Diop in the course of his extensive labors inc1ude: examinations of the epidermis of Egyptian royal mummies recovered during the Auguste Ferdinand Mariette Expedition for verification of melanin content; precise osteo-logical measurements and meticulous studies in the relevant areas of anatomy and physical anthropology; careful examinations and comparisons of modern Upper Egyptian and West African blood-groups; detailed linguistic stud-ies; analysis of the ethnic designations employed by the Kamites themselves; corroborations of distinct African cul-tural traits; documentations of Biblical testimonies and references regarding ethnicity, race and culture; and the writings of early Greek and Roman scholars for descriptions of the physical appearances of the ancient Egyptian people.

Diop firmly believed that “The highest point of Egyptian history was the Nineteenth Dynasty of Ramses II.” Ramses reigned from 1279 to 1213 BCE, more than 3200 years ago. His reign was a time of power and prosperity for the people of Africa’s Nile Valley. The sixty-seven year reign of Ramses the Great was for Kmt an era of general prosperity, stable government and extensive building projects. Ancient deities like Ptah, Re and Set were elevated to high status. The adoration of Amen was restored and his priests reinstated. Major wars were fought with the Libyans, Hittites and their allies. Wondrous temples from Nubia to the Egyptian Delta were carved out of the naked cliffs. Splendid tombs in the hills of western Waset and Abydos were constructed, renovated and beautified. The new Egyptian city of Pi-Ramses made its impressive debut. Ramses was deified in his own lifetime, and through the unrelenting projection of his own incomparable personality made the name Ramses, the Son of Amen-Re, synonymous with kingship for centuries. Ramses II was truly great. He was the towering figure of his age and established the models and set the standards that others used to rule by. In regards to the ethnicity of the great Ramses, Cheikh Anta Diop unhesitatingly threw down the gauntlet, and spoke of him in a language of unmistakable firmness and certitude: “Ramses II was not leucoderm and could have been even less red-haired, because he reigned over a people who instantly massacred red-haired people as soon as they met them, even in the street; these people were considered as strange beings, unhealthy, bearers of bad luck and unfit for life….Ramses II is black. Let’s let him sleep in his black skin, for eternity.” Sadly, the mummy of Ramses II has been more than disturbed. In Dynasty XXI the mummies of Ramses II and Set I, along with other royal mummies, were removed from their tombs and reburied in the cliffs at Deir el-Bahari. There the mummies were discovered by the Department of Antiquities in 1881 and removed to Cairo. Nor, as Diop wished, was the great king allowed to “sleep in his black skin.” He was subjected to many recent observations and experiments. Speaking of the latter, Ivan Van Sertima makes a number of enormously fascinating observations: “One of the things that struck me most about Diop as a person was his absolute honesty. He was never afraid to criticize something African or black once it merited criticism. I have never found him out in any equivocation or exaggeration. He told me twice, both in London and in Atlanta, that there was no question whatsoever of the blackness or Africanness of Ramses II. He told me that he had actually seen the mummy, and that the skin of the mummy was as black as his skin. He said, however, that after it was subjected to gamma rays the skin looked grayish. It had lost its original dark color. Yet he felt that it would still have been possible to establish its ethnicity through his method, the melanin dosage test. A similar method is now in use in the United States. He said that the scientists involved had used far more gamma rays than was necessary for their experiment. He asked for permission to examine a specimen of the mummy’s skin and hair but he’ was refused permission. The authorities said that it would damage the mummy. Later on, after a certain discovery which was covered up, the scientists abandoned the mummy, suppressed all their reports, and circulated a rumor that this was not really the mummy of Ramses II.”

RAMSES THE GREAT AS MILITARIST: THE KADESH BATTLE

Ramses II never tired of reporting about the battle of Kadesh, The official account of the Kadesh Battle is found inscribed on temples in Abydos, Abu Simbel, the Ramesseum, Karnak, Luxor, and two hieratic papyri. It occurred in the fifth year of his reign near the Orontes River in the Bekaa Valley. At this time the Kamite army was organized into four divisions, each named after one of the chief deities of the realm: Ra, Ptah, Set, and Amen. Included in the Egyptian contingent were the King’s pet lion and two of the monarch’s sons. Misled by false intelligence reports, Ramses, with only a small personal bodyguard, soon found himself far ahead of the main body of his troops, and it was precisely at this moment that the enemies of Kmt attacked. Near the Syrian city of Kadesh the battle was joined, and it was only Ramses’ personal valor and courage that saved the Kmt army from total disaster. Gathering a small band around him, Ramses charged into the Hittite lines no less than four times and held his tiny force together until the Ptah division of his army arrived on the scene to rescue the situation. The Monarch thought enough of this battle to have it commemorated on monuments throughout the Black Land. Withdrawing towards the west, the Kamites finally signed a treaty with the Hittites which prevailed for the rest of the Ramses’ lengthy reign.

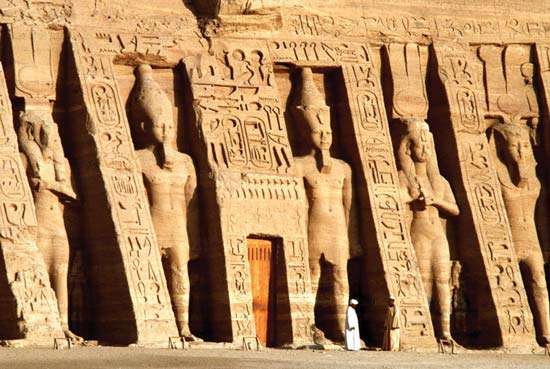

QUEEN OF RAMSES THE GREAT: THE GREAT NEFERTARI

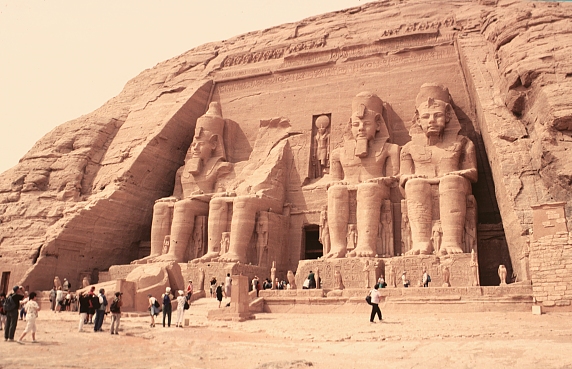

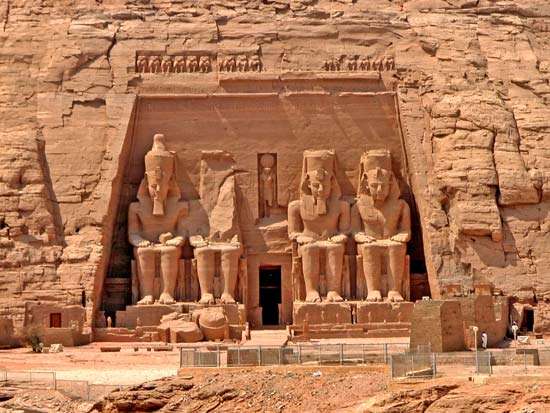

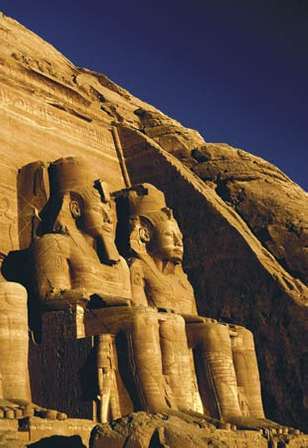

To Ramses II, Queen Nefertari was “The Beautiful Companion.” Nefertari’s two main titles were “King’s Great Wife” and “Mistress of the Two Lands.” The temple of Het-Heru; the northern temple of Abu Simbel, was built by Ramses II to honor this favorite wife, Queen Nefertari. Between the statues of ‘Ramses II are those of Nefertari, and the size of her statues signifies that she will be honored to nearly the same degree as her husband in her relationship to the Deities. Both temples at Abu Simbel were used as storehouses for treasures and tribute exacted from Nubia, thus combining the temples’ essentially religious function with an eminently practical one. Two building inscriptions are found, one in the main hall, and the other on the facade. The first reads: “Ramses, he made it as his monument for the Great King’s wife Nefertari, beloved of Mut–a house hewn in the pure mountain of Nubia, of fine white enduring sandstone, as an eternal work.” The second inscription reads: Ramses-Meriamon, beloved of Amen, like Re, forever, made a house of very great monuments, for the Great King’s wife Nefertari, fair of face….His Majesty commanded to make a house in Nubia hewn in the mountain. Never was the like done before.” After her death Queen Nefertari was worshipped as a divine Osirian, or a soul which had become deified, and under the attributes of Asr (Osiris), Lord of the dead, was adored as a god. Nefertari was housed in a 5,200 square foot tomb, the most splendid in the Valley of the Queens. RAMSES THE GREAT BUILDER: ABU SIMBEL Ramses II commissioned more buildings and had more colossal statues than any other Kamite king, also having his name carved or reliefs cut on many older monuments. Ramses initiated enormous building activities in Nubia. He commissioned temples at Beit-el-Wali, Gerf Hussein, Wadi-es-Sebua, Derr, Abu Simbel and Aksha in Lower Nubia, and at Amara and Barkal in Upper Nubia. The temple of Abu Simbel, one of the largest rock-cut structures in the world, is no doubt a unique piece of architectural work. It is carved into a mountain of sandstone rock on the left bank of the Nile that was held sacred long before Ramses’ temple was cut there. It was dedicated to Re-Harakhte, the god of the rising sun, who is represented as a man with the head of a falcon wearing the solar disc. It is a masterpiece of architectural design and engineering. The whole purpose and position of the temple was devoted to the adoration of the sun at dawn, and it was only at sunrise at certain times of the year that the vast interior was illuminated, when the light penetrated the sanctuary. It must have been for the ancients an unforgettable experience to stand in the main hall at dawn and watch the life-giving light of the sun gradually penetrate into the inner sanctum, the Holy of Holies, of an ancient faith.

On the facade of the temple of Abu Simbel are four colossal seated statues cut out of the living rock. The seated statues, two on each side of the entrance, represent Ramses II wearing the double crown of Kmt. The entrance opens directly into the great hall where two rows of four-square pillars are seen. On the front of these pillars are four gigantic standing statues of the king, again wearing the double crown. Each of the seated colossi are sixty-five feet high, taller than the Colossi of Memnon. On the walls of the great hall, which are thirty feet high, there are scenes and inscriptions concerning religious ceremonies and the monarch’s military activities against the Hittites. The Small Temple of Abu Simbel, contemporary with the Great Temple, was dedicated to the ancient and illustrious goddess Het-Heru and Queen Nefertari. Between 1964 and 1968 both temples were removed to their new location, about 210 miles further away from the river and sixty-five miles higher, at the cost of some ninety million dollars. PI-RAMSES For the international concerns of Kmt and for the regaining of the empire, a capital near Asia and the Mediterranean was needed. To Memphis of the White Walls and Waset, Ramses had the ambition and energy to add a dazzling new urban center. The centerpiece of Pi-Ramses was the former summer palace of Seti I which was added to and enriched by Ramses II. Pi-Ramses was also a place where Kmt’s soldiers and chariots could be housed for military readiness. Ramses took a strong personal interest in the adornment of the city and was constantly in pursuit of new resources for this purpose. He praised himself for his concern for the labor corps working there. He rewarded the overseer with gold as a mark of honor for finding out a block and preparing it for its purpose; he also assured the workmen that he had filled up the storehouse in advance so that ‘each one of you will be cared for monthly. I have filled the storehouse with everything, with bread, meat, cakes, for your food, sandals, linen and much oil, for anointing your heads every ten days and clothing you each year.’”

THE KARNAK TEMPLE COMPLEX

Begun well before the time of Ramses II, the Karnak temple complex grew to become one of the largest sacred sites in the world, encompassing more than 250 acres. The most celebrated and spectacular part of the Karnak temple complex is the grand hypostyle hall. Ramses II completed this hall in a marvelous manner, and it appears as a stupendous forest of columns–exactly 122 of them. The tallest of these columns are about seventy-five feet high, and many of them are decorated with the deeply incised hieroglyphics that became a veritable signature of Ramses II.

THE LUXOR TEMPLE COMPLEX

The magnificent Luxor temple lies just over a mile from the south of the main temple at Karnak. At Luxor, Amen was worshipped in the ithyphallic form of the timeless fertility-god known as Min. The temple is called Luxor, from the Arabic el-Qusur, meaning the Castles, the name given to the village that grew up on the site. The temple is largely the work of Amenhotep III and Ramses II, who added a colonnade court and two obelisks in front of the temple. One remains, the other is in Paris, taken to France in honor of Jean Francois Champollion’s decipherment of Kemetic hieroglyphics. Ramses also had erected at Luxor six colossal statues in his own likeness. Today only four of the statues remain, two seated and two standing.

THE RAMESSEUM

The Ramesseum is the funerary temple of Ramses II located on the west bank of the Nile in Luxor. It was called “The House of Millions of Years of Ramses II in the Estate of Amen.” In the first court of the Ramesseum he set up a granite statue fifty-six feet high, only slightly smaller than the Colossi of Memnon. The gigantic monolith was quarried at Aswan and then ferried down-river to Waset, offloaded, transported several miles to the temple, and erected at the site. Its original weight has been estimated at about 1,000 tons, about three times the weight of one of Hatshepsut’s obelisks at Karnak. It was from the Ramesseum that the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) drew the inspiration for the sonnet in which he wrote, “My name is Ozymandias [Ramses II], king of kings; Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Today, only the head, torso and legs of the statue remain. The rest was destroyed by Christian monks determined to eradicate what they regarded as idolatry.

THE IMMORTAL RAMSES

Having lived vigorously for more than nine decades, Ramses II died in the second month of his sixty-seventh regnal year. There was no final death, however, in the African way of thinking; only gradual decay and periodic renewal. Egypt was perhaps the earliest nation to clearly articulate the purely African notions of resurrection and immortality. As one writer succinctly stated, within the context of Egypt, “If Osiris, the Nile, and all vegetation, might rise again, so might man.” Man could rise, but only if he made God’s words, which were truth, justice and righteousness, manifest on earth. This was fundamental to the African (in this case, Kametic) worldview. Reclaiming for the African world the ancient Kamite heritage (which o

f course includes the knowledge of heroic sovereigns such as Ramses the Great), must be seen as an integral part of the Black liberation movement. It will inspire and direct us. Kmt was the heart and soul of Africa, and we need only glance at her noble traditions, her dignity, humanity and royal splendor to measure our true fall from power. When we examine the civilization of Kmt we note what is perhaps the proudest achievement in all the annals of human history. We must see in Kmt the knowledge that what African people did, African people can do. In this way the great deeds of our illustrious ancestors, including the incomparable Ramses II, are resurrected, and ancient history embraces both what is and what can be, and lays the basis for the forward movement of the African people.

Excerpt from Ramesses III's speech about the war against the Sea Peoples.

Those who reached my boundary, their seed is not; their heart and their soul are finished forever and ever. As for those who had assembled before them on the sea, the full flame was in their front, before the river-mouths, and a wall of metal upon the shore surrounded them. They were dragged, overturned, and laid low upon the beach; slain and made heaps from stern to bow of their galleys, while all their things were cast upon the water. (Thus) I turned back the waters to remember Egypt; when they mention my name in their land, may it consume them, while I sit upon the throne of Harakhte, and the serpent-diadem is fixed upon my head, like Re. I permit not the countries to see the boundaries of Egypt to [--] [among] them. As for the Nine Bows, I have taken away their land and their boundaries; they are added to mine. Their chiefs and their people (come) to me with praise. I carried out the plans of the All-Lord, the august, divine father, lord of the gods. {"The Nine Bows" refers to Egypt's traditional enemies}. The Sea peoples' defeat prevented them from conquering Egypt itself, but it left the Egyptians incapable of defending their possessions in the East, which were colonized by the Philistines, Sidonites and others. The effects of the eclipse of Egyptian power are described in the Wenamen papyrus. Local kings, such as the king of Dor, showed quite open contempt for the ambassador of the Pharaoh. According to this, possibly ficticious account, at the beginning of the 11th century B.C, during the reign of Ramses XI: Wenamen, a priest of the Amen temple at Karnak, sailed in a Phoenician ship to Gebal (Byblos) in order to buy timber for the construction of a solar ship. He carried with him a letter of introduction to Zekharbaal, king of Gebal, a statue of the god Amen and some valuables. In this account of Wenamen's journey, there is still hostilities between the Tjekker (Philistines) and Egypt, as the Tjekers seek to imprison Wenamen.

The countries -- --, the [Northerners] in their isles were disturbed, taken away in the [fray] -- at one time. Not one stood before their hands, from Kheta, Kode, Carchemish, Arvad, Alashia, they were wasted. {The}y {[set up]} a camp in one place in Amor. They desolated his people and his land like that which is not. They came with fire prepared before them, forward to Egypt. Their main support was Peleset, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Denyen, and Weshesh. (These) lands were united, and they laid their hands upon the land as far as the Circle of the Earth. Their hearts were confident, full of their plans.

Now, it happened through this god, the lord of gods, that I was prepared and armed to [trap] them like wild fowl. He furnished my strength and caused my plans to prosper. I went forth, directing these marvelous things. I equipped my frontier in Zahi, prepared before them. The chiefs, the cap-tains of infantry, the nobles, I caused to equip the river-mouths [1], like a strong wall, with warships, galleys, and barges, [--]. They were manned [completely] from bow to stern with valiant warriors bearing their arms, soldiers of all the choicest of Egypt, being like lions roaring upon the mountain-tops. The charioteers were warriors [-- --], and all good officers, ready of hand. Their horses were quivering in their every limb, ready to crush the countries under their feet. I was the valiant Montu, stationed before them, that they might behold the hand-to-hand fighting of my arms. I, king Ramses III, was made a far-striding hero, conscious of his might, valiant to lead his army in the day of battle.

© Copyright BREAKING CHAINS MINISTRY